United States Supreme Court Decision on the Affordable Health Care Act [1]:

The Next Chapter

© Jack Edward Urquhart July 12, 2012

Beirne, Maynard & Parsons, L.L.P.

June 28, 2012, the United States Supreme Court resolved constitutional challenges to two provisions of the Affordable Health Care Act (ACA).[2] The court held that Congress’ power to tax provided authority to enact the “individual mandate,” [3] but Congress overstepped its authority in its planned “Medicaid expansion.”[4] The individual mandate survived intact. The Medicaid expansion also survived, but Congress may not threaten States that do not accept the expansion with the withdrawal of all Medicaid funds.

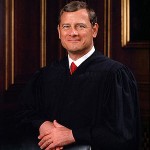

Chief Justice Roberts wrote the controlling opinion. Justice Kennedy wrote a dissent that would have voided the ACA in its entirety, and was joined by Justices Scalia, Thomas and Alito. Justice Ginsburg, while joining Roberts’ ultimate results, argued that the Chief Justice erred in holding that the Commerce and Necessary and Proper clauses did not authorize Congress to enact the individual mandate. Additionally, Justice Ginsburg asserted that Congress had the authority to deny all Medicaid funds to a State that opted out of the ACA Medicaid expansion.

The pre-decision hype was merited, if only by the intriguing opinion authored by the Chief Justice. The ACA was a single vote away from extinction. Roberts literally saved the act. Why he did so is speculative. And the rampant speculation is both interesting and entertaining.

But the different question—How Chief Justice Roberts “saved” the ACA?—is more clearly answered and far more important.

Subtle in tone, the Roberts’ opinion formalizes Congress’ shrinking Article I power. While allowing the individual mandate to survive, it drove a stake through the heart of the federal government’s primary argument for congressional authority to enact the ACA. Roberts rejected the notion that the Commerce Clause,[5] long the foundation of congressional assertions of authority, permitted Congress to enact the individual mandate.

Justice Ginsburg’s strong disagreement reveals an appreciation of how sweepingly Roberts’ assault on the Commerce Clause cuts away congressional authority. She wrote that the Chief Justice’s reading of the Commerce Clause “makes scant sense and is stunningly retrogressive.” She cautioned that it “is a reading that should not have ‘staying power.’” Justice Ginsburg’s passionate clash with the Chief Justice’s view of the Commerce Clause is lengthy, detailed, and powerfully written. But it is a minority view.

And Justice Ginsburg’s fervor confirms that the Chief Justice’s opinion signals a potentially radical departure from prevailing notions of the scope of the Commerce Clause. The Supreme Court appears fully prepared to reexamine the view of the Commerce Clause that has governed since the 1930s.[6]

The Chief Justice also clarifies that central to this reexamination of the Commerce Clause is the Supreme Court’s obligation to maintain the constitutional balance of power between the federal government and the Sovereign States. Chief Justice Roberts’ carefully modulated opinion is among the most effective State’s Rights opinions in recent memory.

The logic of his specific rulings and the opinion that supports them are calmly thunderous affirmations that the Constitution does in fact set defined limits on the power of the federal government. The powers not constitutionally assigned to the federal government belong to the States and the People. Chief Justice Roberts views these founding principles as mandates—not mantras, routinely recited and routinely ignored.

In summary, this is “how”—and probably “why”—Chief Justice Roberts reached his decision as supported by the text of his opinion:

- The role of the Supreme Court in this case was limited to determining whether Congress had the power to enact the individual mandate and the Medicaid expansion. Specifically, the Court could not consider the “wisdom” of the challenged provisions.[7] And it certainly could not judge the wisdom of the ACA as a whole. The merit of the ACA is the responsibility of Congress and the Executive. And, ultimately, is the responsibility of the People who can “throw out” elected officials. The Chief Justice, consistent with this view, spent little time discussing details of the ACA. This is in noted contrast to the other Justices and lower court judges who wrote opinions on the challenged provisions.

- The Court, however, will not abdicate its responsibility to make certain that the federal government does not exceed its constitutionally limited power. While acknowledging the very broad readings the Court has given the Commerce Clause and the appropriate deference the Court owes the Congress and the Executive, the Chief Justice’s vision of the Court’s role dictated that the Court scrutinize the question of whether the individual mandate was truly justified by the Commerce Clause.[8] It was not. Congress exceeded its Commerce Clause power.

- Moving to a secondary argument made by the federal government, Roberts considered congressional authority to tax and spend.[9] Congress did have authority to enact the individual mandate as part of its constitutionally enumerated power to tax and spend. Carefully, the Chief Justice cordoned off notions of an unlimited taxing power.

- The Medicaid expansion fared even less well. Maintaining the steady-understated tone of his opinion, Roberts elegantly skewered the Federal Government’s attempted use of the threat of withholding all Medicaid funds from non-compliant states. Bluntly, he found it unconstitutionally coercive and over-reaching, in violation of the 10th Amendment. Only Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor disagreed. The Medicaid expansion is constitutional, but only if a State can opt out without the “gun to its head” of losing all Medicaid funding.[10]

What is the next chapter?

The next chapter is squarely in the hands of the federal and State governments and the People and imagination is the only limit to available policy issues and options. The following seem significant areas of focus:

- An effort to understand the ACA in its fullness.

- Questioning whether the ACA as a whole, or in part, will produce sustainable improvement to the access of quality medical care.

- Evidenced-based answers to the questions.

- Creative alternatives to massive federal regulation of healthcare that will produce sustainable improvement to the access of quality medical care.

Understanding the ACA

Is the ACA a worthy voyage of discovery in the grand American tradition or is it a fool’s errand? Is it similar to the mission of landing on the moon—challenging but achievable? Or is it a snipe hunt—and the only issue is who will be left holding the bag?

This much is clear. The ACA is aspirational. It is experimental. It is a work-in-progress. This does not doom the Act. It just defines it.

A full understanding of the ACA is impossible. Although it can be read, it is an outline, rather than a complete narrative. It requires, among other things, regulations—many that remain unwritten even as proposals.[11]

The ACA is a massive federal regulatory program.[12] It aspires to comprehensively regulate the health care insurance and health care services markets. As initially printed, the ACA is almost 1,000 pages in length, encompasses 9 Titles and hundreds of laws. It is an excruciatingly tedious read.

It changes hundreds of laws, ranging from the Social Security Act to the Tax Code. It will significantly change the practices of the health insurance industry and the healthcare industry.

Most Americans will feel its impact, and some already have. For example, billions of dollars have been appropriated to allocate money for creating insurance plans for people with pre-existing conditions, off-setting employers’ costs for early retirement health plans, increasing pay for some primary care doctors, and health initiatives like funds for state vaccination programs.

Some healthcare providers have received millions in grants for facility expansion, technology upgrades and a variety of other capital projects to better serve their patients.

At least $13.7 billion has already been spent under the ACA. The largest portion of this has gone to employers, public retirement plans, unions, and others that provide insurance coverage for workers who retire before they are eligible for Medicare. Beneficiaries include the likes of General Electric and the United Automobile Workers. G.E. alone received $39 million.

The following endeavors to describe some of the most significant provisions of the ACA by category:

ACA Tax Provisions

- Tax for failure to comply with mandates.

- Increased Medicare payroll tax deductions and taxation of unearned income, starting in 2013.

- Retiree Drug Subsidy Deduction: Starting in 2013, plan sponsors that provide prescription drug coverage for retirees will no longer be able to deduct the federal retiree drug subsidies on their corporate tax returns.

- Decrease in deducting unreimbursed medical expenses. The percentage of adjusted gross income that unreimbursed medical costs must reach before they are deductible increases from 7.5% of adjusted gross income to 10%.

· Limitation on flex accounts and health savings accounts: Limitations on annual savings of $2,500; ban on reimbursement of OTC drugs other than insulin not prescribed by a doctor from a health reimbursement program; flex accounts and health or medical savings accounts; and increased penalties for certain non-medical distributions from HSAs and MSAs.

· Excise tax on the sale of certain medical devices.

· Annual fee on manufacturers and importers of branded prescription drugs sold to specified government programs.

· Excise tax on certain health plans: Effective 2018 an excise tax on certain “Cadillac” employer-sponsored health insurance plans.

· The annual fee on certain health insurance providers.

· Tax credits for some small employers that pay at least one-half of their employees’ premiums.

- The non-refundable investment tax credit for investments in qualifying therapeutic discovery projects made during tax years beginning 2009 or 2010.

- The refundable premium assistance credit for lower and middle income individuals to purchase health insurance.

- The codification of the economic substance requirement and penalties for failure to comply.

ACA Medicaid Expansion

The ACA expands Medicaid in two ways. It increases the number of people covered and it increases the benefits received. Medicaid will be expanded to provide “the essential health benefits package” to all individuals at or below 133% of the federal poverty level. The federal government will initially fund 100% of the increased cost. The federal funding will then be reduced to 90%.

ACA Health Plans and Insurance Exchanges

Health plans

- Continue dependent child coverage to age 26.

- Preventive Care Coverage for additional preventive care services beginning August 1, 2012.

- Continue to prohibit rescissions and coverage based on medical history.

- Administrative simplification: Effective January 2013, health plans must implement uniform standards and business rules for the electronic exchange of health information in order to reduce paperwork and administrative burdens and costs.

Insurance exchanges

- American health benefit exchange for individuals.

- Small business health option program. In 2017, large employers may use this program.

- The exchanges must offer qualified health plans that provide “essential benefits” unless it is a catastrophic coverage plan.

- An essential benefit package must offer coverage for specific benefit categories:

- Preventive and wellness services, including management of chronic disease.

- Emergency services.

- Hospitalization.

- Maternity and newborn care.

- Mental health and substance-use services.

- Prescription drugs.

- The exchanges must meet certain cost-sharing standards.

- Provide levels of coverage tied to full actuarial value of the services:

- Bronze=60%.

- Silver=70%.

- Gold=80%.

- Platinum=90%

The federal government will establish these exchanges in the absence of State action.

ACA Employers and Employees

- · Summary of Benefits and Coverage: Effective for open enrollments periods beginning September 23, 2012, employers must supply employees with SBCs.

- · Notice of State exchanges: Effective no later than March 1, 2013, employers must provide written notice to current employees and new hires of State Insurance Exchanges. The notice must inform the employees that, if the employer’s share of the total allowed costs of benefits provided under its plan is less than 60%, the employee may be eligible for a premium credit. Regulatory guidance is not yet available on the content of the notice.

- Compliance with new W2 reporting requirements for tax year 2012.

- · Compliance with Medicare withholding changes.

- · Quality of Care Reporting: This applies to non-grandfathered group health plans and insurer. HHS regulations required March 23, 2012 have not issued.

Do these provisions as a whole, or in part, produce sustainable improvement to the access of quality medical care?

Candidly, evidence-based analysis is difficult, if not impossible, to apply. This opinion was tipped-off when the ACA was described as an experimental.

The strongest theoretical support for the ACA addresses “access” to third-party payment for medical services. Logically, the ACA will decrease the number of individuals now classified as uninsured. This assumes Medicaid expansion, affordable insurance programs, including employer-based health insurance plans and insurance exchanges, and consumer choices to purchase a health insurance product.

Accepting a decrease in the number of persons classified as uninsured, the support for sustainability and improvement in the quality of medical care appears simply speculative. Without downplaying the need for reform, reform seems impractical without a sound plan that 1) recognizes that quality of healthcare really depends on the intensely personal relationship between doctor and patient, and 2) both sustainability and access require a significant reduction in the increasing cost of medical care.

Some “wisdom” resides in the premise that State and local governments are in the best position to initiate true health care reform. They are at least closer to the key players in quality healthcare—the patients and the doctors. And they are far more sensitive to issues of cost. They have to be.

Against this are two very persuasive arguments. First, the healthcare crisis may in fact be too great, requiring massive federal intervention. Second, States and local governments have not been prevented from initiating effective health care reform. If they have not met that challenge in the past, why should we look to them for a solution now?

Practically, the “next chapter” should resoundingly recognize that health care reform is needed. Similarly, it should recognize that the ACA includes measures that hold much promise. At the same time, the next chapter must accept that the ACA is an experiment of unprecedented scale. It is not merely poorly understood. It is not understandable. We cannot be sure it is a fool’s errand. We can be sure it lacks the foundation that supported our collective decision to land on the moon.

This all leads in a single direction. The ACA has answers, but is not the answer. The time calls for assertive and, preferably, concerted State and local intervention and initiative. Needless to say, more than resistance and reaction is required. While efforts to resist massive, and questionable, federal regulation are understandable, the time also demands concrete proposals to provide sustainable improvement to the access of quality medical care.